History of The Home

The grand tale of our nation's history is in many ways composed from a procession of small moments.

Blair House has been the site of many such moments, a quiet but significant part of America’s story.

Important decisions are made in small rooms; grand strategies emerge from quiet chats beside the fire or from meetings around a table after the dishes are cleared away.

About the Blairs

Built in 1824, Blair House became politically central in Washington, D.C., the moment the Blair family took up residence in 1837.

Francis Preston Blair was a circuit court clerk from Frankfort, Kentucky, whose editorials in his local newspaper attracted President Andrew Jackson’s attention. Jackson invited Blair to convert the Globe, a failing D.C. newspaper, into a pro-administration publication, and in 1830, Blair, his wife Eliza, and their three children moved to the nation's capital. Seven years later, they took up residence in the former home of Dr. Joseph Lovell, the first surgeon general of the U.S. Army. It would soon become known as Blair House.

As editor of the Globe and the Congressional Globe (the first published proceedings of Congress) with partner John Cook Rives, Blair acquired a good deal of political power. Many political players, including presidents, sought his insight. He was the most influential member of President Jackson's informal group of advisors, the “Kitchen Cabinet,” and remained an important confidant to Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren. Abraham Lincoln also sought Blair’s counsel during his presidency and appointed Blair's eldest son, Montgomery, to his cabinet as Postmaster General.

In 1859, Francis Preston Blair built a home at 1653 Pennsylvania Avenue, next to Blair House, for his daughter Elizabeth and her husband, Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee. This home, known as Lee House, is now an integral part of the Blair House complex.

Becoming The President’s Guest House

The United States Government purchased Blair House in 1942 at the urging of President Franklin Roosevelt when the need for diplomacy grew apace with the American military role in the Second World War.

Previously, guests of the president customarily spent a night in the White House, followed by a hotel or embassy for the remainder of their visit. Winston Churchill’s frequent trips to Washington helped convince President Franklin Roosevelt of the need for official diplomatic housing.

Franklin Roosevelt, Jr., recalls the morning his mother found the prime minister wandering towards the family’s private quarters at 7:30 a.m., trademark cigar in hand, to rouse the sleeping president for more conversation. He met Eleanor first, however, who firmly persuaded him to wait until breakfast.

The President soon approved the purchase of Blair House—which included the Blair family’s furniture, china and silver—and the President’s Guest House was in business.

Find the whole story in the free eBook, To Be Preserved for All Time: The Major and the President Save Blair House.

Historical Events

President Andrew Jackson & the “Kitchen Cabinet”

(1829-1831)

When President Andrew Jackson took office in 1829, his official Cabinet was fractured by factional disputes, largely resulting from the fierce rivalry between Vice President John C. Calhoun and Secretary of State Martin Van Buren. The infighting was so pronounced that the Cabinet became virtually ineffectual, and Jackson stopped holding Cabinet meetings. He turned instead to an unofficial group of trusted friends and advisors, mocked in the rival press as the “Kitchen Cabinet.” Francis Preston Blair was a valued member.

The Kitchen Cabinet played an important role in the Jackson administration until 1831. That year, controversy within the official Cabinet provoked the resignation of Van Buren and Secretary of War John Eaton, which allowed Jackson to request the resignations of all of the remaining members. The Kitchen Cabinet gradually declined with the success of his next official Cabinet, but Jackson’s bond with Blair remained strong to the President’s death in 1842.

The Globe & Congressional Globe

Francis Preston Blair moved to Washington, D.C. at the invitation of President Andrew Jackson, who was seeking an experienced and sympathetic voice to take charge of the pro-administration newspaper, the Globe. Blair had come to the attention of the Jackson administration through a series of supportive articles he had written in his role as the editor of a local paper in Frankfort, Kentucky.

Under his leadership, the Globe became highly successful. In 1834, with partner John C. Rives, Blair began a second publication of Congressional proceedings, the Congressional Globe. It became the Congressional Record in 1873 and is still published today.

Webster-Ashburton Treaty

The 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War left certain sections of the boundary between the United States and Canada undefined. In the first decades of the 19th century, an expanding population in northern Maine led to competitive friction between rival groups of loggers in Maine and New Brunswick. Eventually, the situation heated into a conflict known as the Aroostook War. While the “war” was bloodless, forces were raised on both sides, making clear a pressing need to define the border.

In 1842, President John Tyler’s secretary of state Daniel Webster met with British Foreign Minister Alexander Baring, the first Baron Ashburton, to resolve this. The treaty that resulted, known as the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, clearly defined the borders between Maine and New Brunswick, as well as the Great Lakes area. Additional matters addressed in the treaty concerned matters of extradition between the two nations and agreement on the part of the United States to strengthen its policing of the illegal slave trade.

Secession and General Lee

Within four months of the 1860 presidential election of Republican Abraham Lincoln, South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas seceded from the Union. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces attacked and captured Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Three days later, President Lincoln called up 75,000 militiamen.

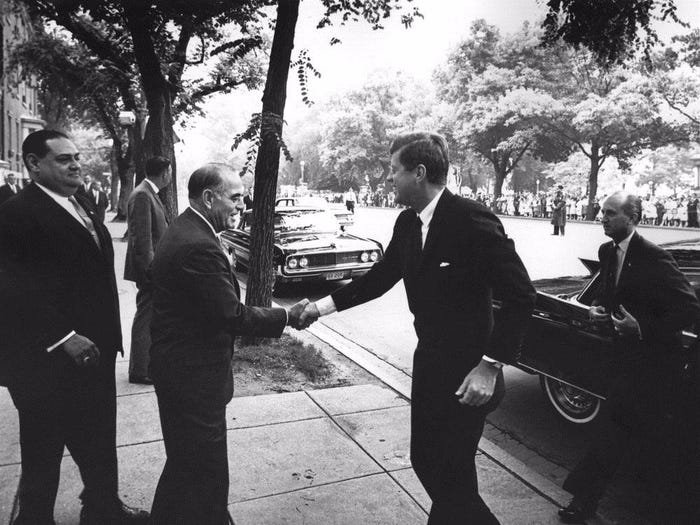

As Colonel of the 2nd Cavalry, Robert E. Lee enjoyed a celebrated reputation. Acting at the behest of his friend President Lincoln, Francis Preston Blair offered command of the Union Army to Lee in a meeting in Blair House. Knowing that the secession of his native Virginia was imminent, Lee declined the offer and resigned his commission in the U.S. Army, taking command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia two days later.

General Tecumseh Sherman

Born in 1820, General William Tecumseh Sherman was educated at West Point. An orphan at an early age, he was raised by Thomas Ewing, who served as the U.S. senator from Ohio (twice), the Secretary of the Treasury, and the first Secretary of the Interior. Sherman married Ewing’s daughter, Ellen, in a ceremony at Blair House in 1850; Ewing was renting Blair House at the time.

Sherman served as a captain in the artillery in the Mexican War but resigned his commission in 1853. He tried his hand at banking and law, but was largely unsuccessful. He served for a time as the superintendent of a military school in Louisiana (now Louisiana State University). When Louisiana seceded from the Union, Sherman left, moving first to St. Louis and then volunteering for the Union Army. He gained considerable notoriety for a series of campaigns known colloquially as “Sherman’s March to the Sea.” In the course of this campaign, he took and largely destroyed Atlanta, then proceeded to Savannah. The transit of his troops was particularly destructive, and the renown he enjoyed in the North was matched by the enmity felt by many in the South.

Sherman retired from the army in 1884 and died in New York City in 1891.

World War II

The complexity of the World War II Allied effort and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s leadership brought extraordinary numbers of official visitors and heads of state to the White House. The custom of the day was for heads of state to spend the first night at the White House, then move to a hotel for the duration of their stay. However, space was limited, and Washington hotels were constantly booked.

In early 1942, Stanley Woodward, Chief of Protocol for the Roosevelt administration, initially arranged to rent Blair House before it was eventually purchased by the State Department later that year. In May, President Manuel Prado of Peru was the first guest. In 1943, when the number of guests increased beyond the capacity of Blair House, Lee House was purchased to provide additional space for foreign leaders visiting the White House.

Truman at Blair House

The Truman White House

By the time Harry S. Truman became president, the White House was badly in need of renovation. Spurred by swaying chandeliers and wobbling floors, Truman ordered an inspection in the winter of 1947. The news was even worse than he thought. The second floor of the White House living quarters and the ceiling in the state dining room were dangerously unstable. Emergency supports were installed, but in the summer of 1948 the floors were coming apart under their feet.

It was clear the house would have to be gutted and rebuilt. Throughout the four-year renovation, Truman and his family lived in Blair House—earning Blair House the nickname “The Truman White House.”

The Truman Doctrine

The end of World War II created a great deal of international turmoil. Greece was facing a Communist-led insurrection, and Turkey was under considerable pressure from the Soviet Union to share control of the Dardanelles straits. Great Britain had been providing aid but could not continue due to postwar expenses.

Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson was convinced that if Communism overtook Greece and Turkey, it could spread to nearby nations. Later known as the Domino Theory, this precept persuaded President Truman in March l947 to appear before a joint session of Congress and ask for $400 million in military and economic assistance for Greece and Turkey. He said, “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.”

This stance, known as the Truman Doctrine, guided American foreign policy through the 40 years of the Cold War that would follow. While its ultimate consequences remain the subject of much debate, the Truman Doctrine signaled the beginning of active U.S. engagement with foreign policy and the end of U.S. isolationism.

The Marshall Plan

On April 3, 1948, President Truman signed into law The European Recovery Program, also known as the Marshall Plan, which authorized more than $13B in U.S. aid to flow to 16 war-torn European nations to improve their agricultural and industrial production and rebuild housing, medical, and transportation facilities.

Truman Assassination Attempt

On November 1, 1950, a pair of Puerto Rican nationalists made an attempt on President Truman’s life at Blair House, his temporary residence. The two men, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, sought to bring attention to the Puerto Rican independence movement.

The men attempted to shoot their way into the house from the front door of Blair House. A gun battle ensued on and around the front steps with White House police officers and Secret Service agents. President Truman was awakened in an upstairs bedroom by the sound of gunfire. He rushed to the window, but a guard shouted at him to take cover.

When the dust cleared, three White House policemen were injured, Torresola was killed, and Collazo was wounded. Private Leslie Coffelt, who fired the bullet that killed Torresola, died later that day from his wounds. His badge is displayed in his honor in the Blair House security office.

For more information, visit the Truman Library’s website at www.trumanlibrary.org.